How Did Akenaten Change Art How Did Akhenaten Change Art

Of all the pharaohs who ruled ancient Egypt, there is one in particular that stands out from the residue. Over the course of his 17-yr reign (1353-1336 BCE), Akhenaten spearheaded a cultural, religious, and artistic revolution that rattled the country, throwing thousands of years of tradition out the window and imposing a new world order. After his expiry his name was omitted from the male monarch lists, his images desecrated and destroyed. From the surviving fragments of evidence, Egyptologists have pieced together the story of his life and reign, a period of spiritual upheaval and experimentation unlike whatever other in Egyptian history. Nether his supervision, Egyptian art underwent a monumental transformation, with centuries of rigid convention abandoned in favor of a new, highly stylized creative approach imbued with divine pregnant.

Statue of Akhenaten

Early REIGN OF AMENHOTEP Iv

The 2nd son of Pharaoh Amenhotep 3, Akhenaten (originally Amenhotep IV) was never meant to be king. His elderberry brother, Prince Thutmose, was heir apparent, but after his untimely demise, young Amenhotep found himself thrust into the political spotlight. Post-obit a brief period of co-regency, Amenhotep 3 died in 1353 BCE, and Amenhotep IV ascended to the throne. With his Corking Wife Nefertiti by his side, the new pharaoh began what appeared to be a conventional reign: he defended monuments to Amun, added to the temple complex at Karnak, and even held a Sed festival in Regnal Year 3. However, Amenhotep IV'south rule was anything only ordinary, and before long the king began to let his truthful colors show. The pharaoh was a fanatical devotee of Aten, a deity representing the concrete form of the dominicus disk. Unlike most other Egyptian gods and goddesses, Aten had no man characteristics and took no anthropomorphic form. Nether Amenhotep's management, this fringe cult before long became the largest religious sect in Arab republic of egypt.

In Regnal Yr 5, the pharaoh dropped all pretense & declared Aten the official land deity of Egypt.

In Regnal Year 5, the pharaoh dropped all pretense and declared Aten the official land deity of Egypt, directing focus and funding away from the Amun priesthood to the cult of the sunday disk. He even changed his proper name from Amenhotep ('Amun is Satisfied') to Akhenaten ('Effective for the Aten,') and ordered the structure of a new capital city, Akhetaten ('The Horizon of Aten') in the desert. Located at the mod site of Tell el-Amarna, Akhetaten was situated between the aboriginal Egyptian cities of Thebes and Memphis on the e banking concern of the Nile.

ARCHITECTURE OF THE AMARNA Menstruum

Non long after coming to power, Akhenaten/Amenhotep 4 commissioned the construction of a new temple complex next to the one at Karnak (modernistic-24-hour interval Luxor). This new project, even so, was a completely separate entity from the temple to Amun, made clear by the fact that the site was located outside of Karnak'south perimeter. Named Gempaaten ('The Aten is Establish'), Amenhotep'due south new temple circuitous was unlike any that had come before information technology. Instead of being comprised of private, closed-in sanctuaries, the open-air courtyards at Gempaaten immune Aten's sunlight to catamenia directly into the complex.

Smaller Aten Temple, Amarna

Following in the footsteps of Gempaaten, the Peachy Aten Temple in Amarna was another prime number example of an "open-air" temple. Surrounded by a large enclosure wall, the temple complex consisted of 2 primary structures: the Sanctuary, located in the eastern section of the complex, and the Long Temple, located in the western section. The fact that this temple was arranged on an east-west axis was itself a nod to the path that Aten took beyond the heaven each day. The Sanctuary was equanimous of two courts, the 2nd of which was open to the air and housed the chantry where Akhenaten and Nefertiti would present their private offerings to the sun disk. The Long Temple consisted of a columned court and more 900 pocket-sized, open-air altars where priests would fire offerings to the Aten. North of the Great Aten Temple was a 2nd, smaller temple, situated in the center of Amarna closer to the palace and king's royal residence. This 2nd temple too followed the layout of Gempaaten and the Corking Aten Temple, synthetic so that it was exposed to direct sunlight at all times.

Amarna'south multiple palaces were constructed of mudbrick and painted with colorful, highly decorative scenes of plants, wildlife, and the royal family unit. These structures included many open up courts and columned porticos, equally well every bit big courtyards decorated with colossal stone statues of Akhenaten and Nefertiti.

PORTRAITURE OF AKHENATEN

Artifacts from Akhenaten's reign are instantly recognizable for their unique creative manner. Among the almost striking of these pieces are those depicting the king himself, many of which accept atomic number 82 Egyptologists to question the state of the pharaoh's health and concrete advent. A prime example comes from Gempaaten: an enormous, full-trunk statue of Akhenaten exhibiting some peculiar characteristics. The male monarch's face up is long and thin, with slit eyes and large, total lips. His effigy is every bit strange and out-of-proportion, with spindly arms, long fingers, a paunch, and feminine hips and breasts. This particular statue is fragmentary, cut the pharaoh off at the knees, but from other depictions of Akhenaten that have survived, it can be inferred that the pharaoh'due south legs tapered out from large thighs to thin calves catastrophe in elongated feet. At showtime glance, such a statue is shocking, as information technology strays so far from the path of typical Egyptian artistic convention. Instead of presenting the image of a young, fit, virile male monarch, creative representations of Akhenaten convey a very unlike message. With such strange bodily proportions and facial features, the pharaoh comes across as weak, sickly, and effeminate.

Jumbo Statue of Amenhotep 4

Why did Akhenaten cull to be presented to his subjects like this? As pharaoh, he had complete control over the production and distribution of artwork and, therefore, was certainly the driving force behind such bold creative choices. Statues like the Gempaaten colossi take acquired many historians to speculate about Akhenaten'due south life and the possibility of the pharaoh being affected by a genetic disorder. Generations of inbreeding and brother-sister marriages during the 18th Dynasty make this theory a very real possibility. Nonetheless, most Egyptologists debate that Akhenaten'south striking visage has more than to do with religious symbolism than capturing the king's literal physical likeness.

Like many of his predecessors, Akhenaten believed himself to be a living god. While most Egyptian pharaohs aligned themselves with the gods of the traditional Egyptian pantheon such as Horus, Akhenaten fittingly decided to associate himself with Aten; one of the king's many epithets was 'The Dazzling Aten,' and he believed himself to exist the lord's day disk's physical manifestation on earth. Different other Egyptian deities, Aten was neuter; the lord's day disk was a concrete object with no discernable sexual practice. It is reasonable to believe, therefore, that Akhenaten (a form of the deity itself) chose to draw himself in a similarly androgynous way. Historical and archaeological evidence has clearly proven that Akhenaten was a fertile male (he had at least six daughters and one son), but the inclusion of such hitting female traits in artistic depictions of the king sent a powerful message, connecting the pharaoh to the essence of Aten itself.

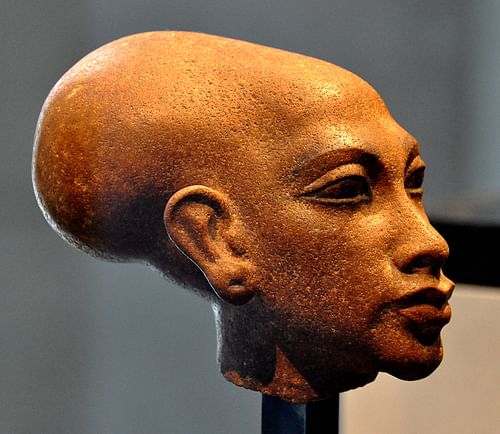

Queen Nefertiti

Over the course of Akhenaten's reign, it is known that at least ii different sculptors were employed in the service of the king. The offset, a homo named Bak, is mainly credited with the earliest and nearly radical Amarna-style pieces (i.east. the Gempaaten colossi). Information technology has been suggested the period immediately following Regnal Year five served as a sort of "experimentation menstruation" in which Akhenaten tried to push the boundaries of Egyptian creative convention as far as he could, equally a upshot producing some of the most radical and stylized pieces of the Amarna Menstruum. In the later years of Akhenaten's dominion, Bak was replaced by some other sculptor, Thutmose, who had a more measured approach to his work. Items recovered from Thutmose's workshop prove that the sculptor favored a more realistic, less-exaggerated style than his predecessor, best exemplified by his iconic bust of Nefertiti on brandish in Berlin.

IMAGES OF NEFERTITI & THE Majestic FAMILY

One of the most touching and fascinating aspects of art during the Amarna Period is how Akhenaten and his family presented themselves. In traditional Egyptian artwork, the figures are usually quite potent and composed, often depicted participating in solemn religious ceremonies or political events. Seldom were the regal family unit shown in a casual setting, spending time together in scenes from their daily life. During the reign of Akhenaten, however, all this inverse. The pharaoh was well-nigh e'er accompanied past his daughters, and his Not bad Wife Nefertiti was always past his side. The family was frequently shown offer to the Aten, but there are also scenes of the regal family eating together and relaxing in the palace. The immature princesses were oftentimes captured playing around their parents' thrones, or cradled in their laps. Nefertiti (and her daughters) were also painted with the same red ochre peel tone as her husband, a color typically reserved for males, and, along with the pharaoh, had unusually detailed easily and feet (before this point, the Egyptians had made no effort to distinguish between correct and left appendages).

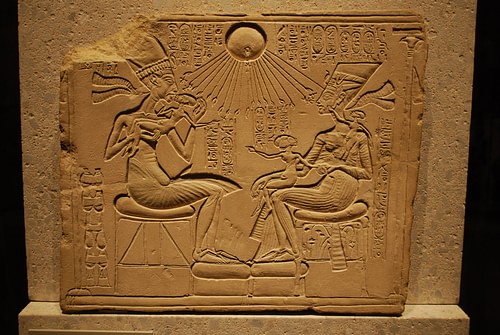

Akhenaten & Nefertiti

In that location exist countless stelae and carvings of Akhenaten and Nefertiti adoring on ane another and holding hands: in one example the queen even sits on her hubby's lap. The couple likewise frequently appears in relief scenes showing them riding chariots together and bestowing gifts on their subject from the "Window of Appearances" in their Amarna palace. This kind of affectionate, realistically-casual portrayal of a pharaoh was unprecedented in Egyptian history.

Similarly unheard of was the symbolic precedence given to Queen Nefertiti in the fine art of the Amarna Period. Instead of being portrayed as a scaled-down female effigy standing behind her husband, Nefertiti was oft presented at the aforementioned scale equally Akhenaten, a bold creative option denoting her bang-up importance and influence in court. And important she was: during the terminal few years of Akhenaten's reign, he appointed Nefertiti as his official co-regent, substantially making her a second king of Egypt on completely equal footing with him.

Akhenaten and the Majestic Family unit Blessed by Aten

To further emphasize both her elevated position and the couple's close relationship, early creative depictions of Akhenaten and Nefertiti portray the king and queen as nearly identical figures. Only a few discrete markers existed to differentiate the two rulers, such every bit crowns (Akhenaten favored the thousand hat headdress while Nefertiti favored a flat-topped blue crown), wig styles (variations of the cropped "Nubian-fashion" wig were popular with both husband and wife), and the length and/or mode of their garments. This bold pick was, once more, spurred on by religious symbolism.

By appearing as identical figures, Akhenaten and Nefertiti were aligning themselves with the twin deities Shu and Tefnut, respectively. Nefertiti'due south aforementioned apartment-topped headdress was traditionally associated with the goddess Tefnut. Akhenaten clearly wanted to acquaintance himself and his queen with these primordial creation deities, who, complementary to the Aten, represented forces of life and rebirth. The rex and queen, in essence, became the "Male parent" and "Mother" of the world and heavens, putting them in a divine triad with Aten. Just as depictions of the pharaoh became more toned-down and realistic during the later years of his reign, the tendency of the king and queen to appear as identical figures faded, although their divine association with the twin deities remained in place.

Girl of Akhenaten

When it comes to the private tombs and monuments of Amarna's non-royal inhabitants, images of the royal family play an interesting function. Where one time there would have been images of Horus, Amun, Isis, and other traditional deities lining the walls of elite burying chambers, now stood images of Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their children. Of course, images of Aten were always present, and the sunday deejay always took precedence over whatever human characters depicted alongside information technology. However, during the Amarna menses images of the royal family completely replaced images of the gods that had decorated Egyptian tombs for centuries. Even on the pharaoh'south ain stone sarcophagus, images of Nefertiti replaced those of traditional goddesses. Akhenaten, by associating himself with Shu and the Aten, and Nefertiti with Tefnut, had effectively presented himself and his family equally living gods. What need was there, so, for images of other deities on the walls of his subjects' tombs? The pharaoh, his queen, and their offspring were a sacred extension of Aten on earth and therefore expected to be worshipped in their ain correct and to act as intermediaries between Aten and the mutual man.

THE END OF A DYNASTY

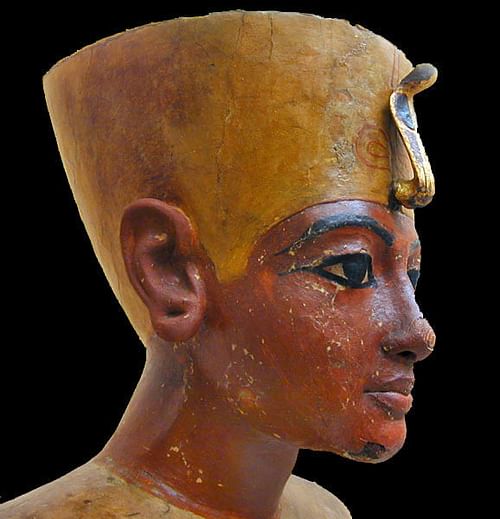

Later on 17 years on the throne, Pharaoh Akhenaten died in 1336 BCE. He was succeeded by the mysterious Smenkhkare (a short-lived pharaoh many Egyptologists believe to have been Nefertiti), who in plough was succeeded by Akhenaten'south immature son Tutankhaten. Post-obit Akhenaten's death, the Egyptian people were quick to voice their opposition to the "heretic" rex's radical religious reforms. Favoring the stability of the onetime order, Tutankhaten moved the capital letter back to Memphis and reinstated the worship of Arab republic of egypt's polytheistic pantheon. Inside a few years, Amarna, Akhenaten's glorious 'Horizon of the Aten' had been completely abandoned, its king and queen buried and forgotten. In a further try to altitude himself from his father'south legacy, the boy male monarch inverse his proper noun from Tutankhaten ('The Living Image of Aten') to Tutankhamun ('The Living Image of Amun'). His wife and half-sis, Ankhesenpaaten, too followed suit, rebranding herself as Ankhesenamun ('Her Life is of Amun').

Tutankhamun

During his reign, Pharaoh Tutankhamun fabricated groovy strides towards restoring Egypt to its pre-Amarna state, a campaign championed past the subsequent kings Ay and Horemheb. While Amarna-fashion fine art continued to be produced during this transitional catamenia (especially evident in the murals decorating Tutankhamun'due south burial sleeping accommodation), ultimately artistic tradition prevailed and Egyptian fine art from the 19th Dynasty and across largely adhered to historical conventions. With the death of Pharaoh Horemheb in 1292 BCE came the end of the 18th Dynasty itself: Horemheb's heir Ramesses I would found a new dynastic line, ushering Egypt into a gold age of armed services might and economic prosperity. In less than 50 years, nearly every trace of Akhenaten, his controversial reign, and the artistic conventions that defined it had been wiped from beingness.

This article has been reviewed for accurateness, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1110/the-art-of-the-amarna-period/

0 Response to "How Did Akenaten Change Art How Did Akhenaten Change Art"

Post a Comment